What is a Congenital Heart Defect?

A congenital heart defect is an abnormality in any part of the heart that is present at birth. Heart defects originate in the early weeks of pregnancy when the heart is forming.

How do heart defects affect a child?

Some babies and children with heart defects experience no symptoms. The heart defect may be diagnosed if the health care provider hears an abnormal sound, called a murmur. Children with normal hearts also can have heart murmurs, called innocent or functional murmurs. A provider may suggest tests to rule out a heart defect.

Certain heart defects can cause congestive heart failure. In this condition, the heart can’t pump adequate blood to the lungs or other parts of the body. It can lead to fluid build-up in the heart, lungs and other parts of the body. An affected child may experience a rapid heartbeat and breathing difficulties, especially during exercise. Infants may experience these difficulties during feeding, sometimes resulting in poor weight gain.

Some heart defects result in a pale grayish or bluish coloring of the skin called cyanosis. This usually appears soon after birth or during infancy and should be evaluated immediately by a health care provider. On occasion, cyanosis may be delayed until later in childhood. Cyanosis is a sign of defects that prevent the blood from getting enough oxygen. Children with cyanosis may tire easily. Symptoms, such as shortness of breath and fainting, often worsen when the child exerts himself. Some youngsters may squat frequently to ease their shortness of breath.

What tests are used to diagnose heart defects?

Babies and children who are suspected of having a heart defect are usually referred to a pediatric cardiologist. This doctor can do a physical examination and often recommends one or more of the following tests:

- Chest X-ray

- Electrocardiogram

- Echocardiogram

What causes congenital heart defects?

In most cases, scientists do not know what makes a baby”s heart develop abnormally. Genetic and environmental factors appear to play roles.

Environmental factors can contribute to congenital heart defects. Women who contract rubella during the first three months of pregnancy have a high risk of having a baby with a heart defect. Other viral infections, such as the flu, also may contribute, as may exposure to certain industrial chemicals. Some studies suggest that drinking alcohol or using cocaine in pregnancy may increase the risk of heart defects.

Certain medications increase the risk. These include:

- The acne medication Isotretinoin.

- Certain anti-seizure medications.

- Some studies suggest that first-trimester use of antibiotics used to treat urinary-tract infections, may increase the risk of heart defects.

Certain chronic illnesses in the mother, such as diabetes, may contribute to heart defects. However, women with diabetes can reduce their risk by making sure their blood sugar levels are well controlled before becoming pregnant.

Heart defects can be part of a wider pattern of birth defects. For example, at least 30 percent of children with chromosomal abnormalities, such as Down syndrome (intellectual disabilities and physical birth defects) and Turner syndrome (short stature and lack of sexual development), have heart defects. Children with Down syndrome, Turner syndrome and certain other chromosomal abnormalities should be routinely evaluated for heart defects.

What are some of the most common heart defects, and how are they treated?

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA):

Before birth, a large artery (ductus arteriosus) lets the blood bypass the lungs because the fetus gets its oxygen through the placenta. The ductus normally closes soon after birth so that blood can travel to the lungs and pick up oxygen. If it doesn’t close, the baby may develop heart failure. This problem occurs most frequently in premature babies. Treatment with medicine during the early days of life often can close the ductus. If that doesn”t work, surgery is needed.

Septal defect:

This is a hole in the wall (septum) that divides the right and left sides of the heart. A hole in the wall between the heart’s two upper chambers is called an atrial septal defect, while a hole between the lower chambers is called a ventricular septal defect. These defects can cause the blood to circulate improperly, so the heart has to work harder. A surgeon can close an atrial or ventricular septal defect by sewing or patching the hole.

Coarctation of the aorta:

Part of the aorta, the large artery that sends blood from the heart to the rest of the body, may be too narrow for the blood to flow evenly. A surgeon can cut away the narrow part and sew the open ends together, replace the constricted section with man-made material, or patch it with part of a blood vessel taken from elsewhere in the body.

Heart valve abnormalities:

Some babies are born with heart valves that do not close normally or are narrowed or blocked, so blood can’t flow smoothly. Surgeons usually can repair the valves or replace them with man-made ones. Balloons on catheters also are frequently used to fix faulty valves.

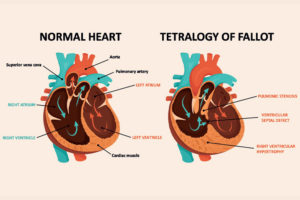

Tetralogy of Fallot:

This combination of four heart defects keeps some blood from getting to the lungs. As a result, the blood that is pumped to the body may not have enough oxygen. Affected babies have episodes of cyanosis and may grow poorly. This defect is usually surgically repaired in the early months of life.

Transposition of the great arteries:

Transposition occurs when the positions of the two major arteries leaving the heart are reversed, so that each arises from the wrong pumping chamber. Affected newborns suffer from severe cyanosis due to a lack of oxygen in the blood. Recent surgical advances make it possible to correct this serious defect in the newborn period.

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome:

This combination of defects results in a left ventricle (the heart’s main pumping chamber) that is too small to support life. Without treatment, this defect is usually fatal in the first few weeks of life. However, over the last 25 years, survival rates have dramatically improved with new surgical procedures and, less frequently, heart transplants.

At what age do children have surgery to repair heart defects?

Many children who require surgical repair of heart defects now undergo surgery in the first months of life. Until recently, it was often necessary to make temporary repairs and postpone corrective surgery until later in childhood. Now, early corrective surgery often prevents development of additional complications and allows the child to live a normal life.

Following surgery, children should have periodic heart checkups with a cardiologist. Children and adults with certain heart defects, even after surgical repair, remain at increased risk of infection involving the heart and its valves.

Is there a prenatal test for congenital heart defects?

Echocardiography can be used before birth to accurately identify many heart defects. If this test shows that a fetus’s heart is beating too fast or too slowly, the mother can be treated with medications that may restore a normal heart rhythm in the fetus. This treatment often prevents fetal heart failure. In other cases, where the heart defect can”t be treated before birth, parents and providers can plan the delivery so that the baby can receive necessary evaluation and treatment soon after birth.

Can congenital heart defects be prevented?

Most congenital heart defects cannot be prevented. However, there are some steps a woman can take before and during pregnancy that may help reduce the risk of having a baby with a heart defect:

- Take a multivitamin containing 400 micrograms of folic acid daily, starting before pregnancy.

- Go for a preconception visit and get a test for immunity to rubella and be vaccinated if she is not immune.

- Women with diabetes and phenylketonuria (PKU), should discuss adjusting their medications and eating habits to keep these conditions under control before and during pregnancy.

- Avoid people who have the flu or other illnesses with fever.

Avoid exposure to organic solvents, used in products such as paints, varnishes and degreasing/cleaning agents.